‘Where Black Bodies Dream’: Creating Your Own Utopia with Haitian Artist Adler Guerrier

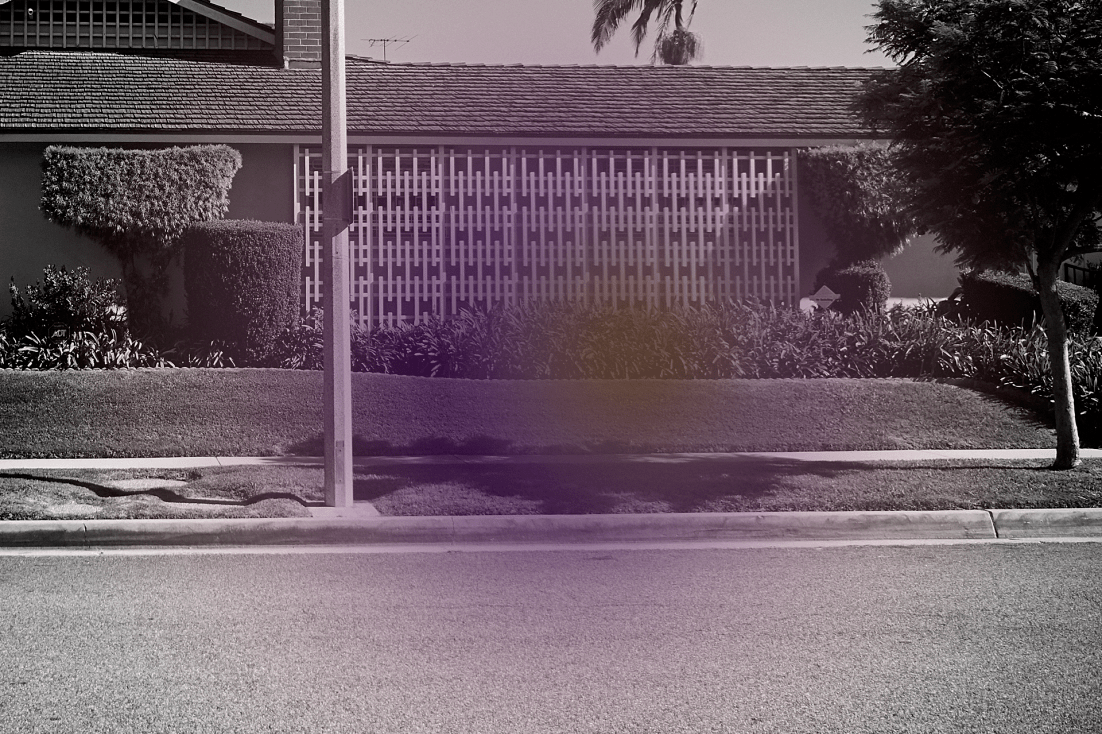

Adler Guerrier, Untitled (Deployed conditionally and sunsetted; Underground), 2017

One definition of heaven is a place of utmost happiness, something enjoyable and pleasant. If you had heaven here on Earth, in this very moment, would you even recognize it? Because you do—we all do—have access to creating utopia in our everyday lives. For proof, look no further than the photography and collages of Miami-based artist Adler Guerrier.

Born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, artist Guerrier is a master at identifying moments of paradise in familiar, African diasporic scenes—from a palm tree–lined block in Los Angeles, to the stillness outside a hair salon, to foliage in a Miami park. His work documents what he calls the spaces in between black and brown bodies, “where brown bodies and black bodies dream, or smell, they whisper, make plans.”

This month, Guerrier was among 83 international artists to open the 13th annual Havana Biennial, in Cuba; and next month, he will join Ebony G. Patterson, Firelei Báez, and other Carribbean artists in the Museum of the African Diaspora’s Coffee, Rhum, Sugar & Gold: A Post Colonial Paradox, in San Francisco.

Below, Guerrier breaks down the art of finding and photographing utopia in everyday life. (Hint: It’s all in your perspective.)

AMIRAH MERCER: I was first introduced to your work by your 2018 exhibit at the California African American Museum, Conditions and Forms for blk Longevity. It was the first time I had seen an artist effectively express blackness without having a black person in the work.

ADLER GUERRIER: It’s so good to hear this, because this domain of blackness must touch all, must encompass all—and the way we live, our house, the way we eat, the food that we grow, the culture that we build, those are connected to places that reflect us. I guess the true test of that is if another can feel this blackness natively by looking at these images and these works. Then it’s a little more true. Before that, it’s more of a proposition on my part.

It’s a work that’s being created within a perspective. [As a writer], your perspective is your hand or your pencil or the piece of paper, and looking at your paper will reflect a particular experience of your blackness or a collective blackness for that matter. So therefore, the shaping of a garden can do that, too—the framing of an image can do it, and the fabric we wear can do it, etcetera, etcetera.

The show at CAAM reflected images that were photographing simultaneously Miami and LA, but there are moments where I think the subjectivity within them would be familiar to someone who lives in Jamaica or Haiti or maybe even Ghana. We are not just formed spatially, we are not just formed within the hard line of where we have been and where we happen to be—there’s a lot of circumstance and there’s a lot of choice, and the combination of all these is expressed spatially, temporally, and even presents itself in plants and trees and other things.

So that focus on not leading with figurative depiction, but depicting the space right next to that, depicting the space in between black bodies, or next to black and brown bodies, or that envelop brown bodies, and where brown bodies and black bodies dream, or smell, they whisper, make plans—those spaces are very necessary to this moment of blackness. So that’s kind of been my focus for a while in my practice.

Adler Guerrier, Untitled (After Evans), 2017

AMIRAH: How did you come to focus on space and location as a way to capture the spirit of a people?

ADLER: I studied architecture at a magnet program in high school, and I did a little bit more in college before I transferred to art. Architecture is very often the product of how bodies use a space—a building, pieces of furniture, hallways, bedrooms, living rooms. And the decision that the architect makes to program a building or a house will hopefully reflect the client that the architect is working for—even if those people change over time or other people live in this house, this structure will serve them.

There’s an embedded narrative within architecture. When we walk to a new place, we can get a sense of character of who lived there, even without seeing the people. And we may be totally wrong, but nevertheless, there often is enough layered information—like, for example, the aroma coming from kitchen windows or the flag that’s hanging outside the house—to give us clues into who these people are and when those people are, as well.

I don’t do straight-on portraiture or biographical work because I tend to be interested in what I imagine is the experience of five or six people, or a dozen people, who walk down a particular street or who crouch by a particular flower on the sidewalk. There’s something comforting in knowing that commonalities between us can be embedded in a wonderful flower that’s giving a wonderful aroma on the sidewalk that dozens of people experienced.

AMIRAH: Do you feel a responsibility to capture a certain location—which someone with a different perspective or different set of biases might think of as lower status—and reveal the beauty in that place?

ADLER: That’s an interesting phrasing. I would say it’s not a ‘responsibility’ so much as a ‘challenge.’ I feel that the greater challenge is to actually prove that where you live matters. The proverb the grass is always greener on the other side of this proverbial fence—this statement is not that your grass is less green than the other side, but that there’s more value to this other space. But it implies that your grass is green as well. So how can another theory put emphasis on your grass, that is still green?

One of the challenges that I really like to take on is this notion that we can enjoy [our lives]. There’s a welcoming to the notion of living well—which may require a kind of problem-solving in less-than-ideal conditions. And less of the hero or leader who comes in and feeds all the children and liberates the people. Some of the work we need is to help us understand how to live every day, so that we can take a greater step toward well being. We have to be able to appreciate what it means to live well.

We need to enjoy notions of heaven, of utopia. There’s politics, disparities, war, injustices, brutality, violence—you can make a long list. But every once in a while, there are particular times when people can enjoy tea in the afternoon, a cookie, and a breeze passing through fragrant flowers. That particular reality is an everyday utopian one. And I try to connect to that often.

From Conditions and Forms for blk Longevity, Adler Guerrier’s 2018 exhibit at CAAM.

AMIRAH: I’ve noticed that through line of utopia in your work.

ADLER: If you think of various torrents in time, a very simple one for me is the reason why my grandparents on both sides of my family worked and gave my parents help—so that their grandkids could enjoy life and be freer and more able to enjoy what the world offers. I feel a kind of responsibility, if there’s a responsibility to be felt, to that labor, that quotidian labor that existed in time. I want to move toward the place where I can live in a manner that reflects the goals of my ancestors who wanted this for me.

So that’s why I focus on these everyday or I’ll even say low wins that can be enjoyed daily. I believe they are partly the point of life in a way. Being a millionaire or billionaire, that doesn’t really matter. I think it matters more that we enjoy roses and drink lemonade as often as possible. I think that matters more. ‘Today I can have lemonade and I have an extra 10 minutes to enjoy these roses.’ That’s an important thing.

AMIRAH: When did you last define freedom for yourself?

ADLER: [Laughs] Within this interview I might have, to tell the truth. I think of what we have to do to give ourselves a bit more space to enjoy roses and lemonade—that is, thinking about greater liberties. I think freedom is our birthright as humans, and we sometimes curtail our desires for freedom because it infringes on another. We must collectively redefine freedom so that we can actually enjoy it together.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.